| Le site web Alexandre Dumas père | The Alexandre Dumas père Web Site | |||

|

||||

| Dumas|Oeuvres|Gens|Galerie|Liens | Dumas|Works|People|Gallery|Links | |||

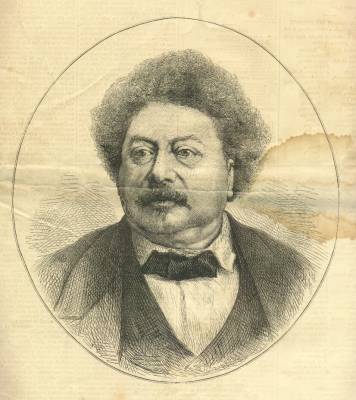

WE print on the first page of the present number a portrait of the great

romance writer and dramatist, whose death is an event of so much importance as to cause a profound

sensation even in the midst of the desperate struggle now in progress abroad. M. Dumas came of a

strangely mingled stock, which may account for the originality of his genius. His grandfather,

the Marquis de Pailleterie, belonged to the old noblesse of France, his grandmother was a

St. Domingo negress. His father,

M. Alexandre Davy Dumas,

served with distinction in the wars of

the First Napoleon, but after his death his family seems to have fallen into comparative poverty.

The subject of our present memoir was born at Villers-Cotterets, near Soissons, in 1803, and might

have been consigned to a lot of utter obscurity but for the kindness of General Foy. The young

Dumas possessed an accomplishment which is not always associated with literary genius, —he

wrote an excellent hand, and thus obtained a clerkship in the office of the Duke of Orleans's

secretary, with a salary of about £ 50 a year. England

may claim the honor of first stimulating his genius. He had already written a forgotten volume

called

"Nouvelles,"

but it was the sight of Charles Kemble in Hamlet which

set him in the path of success. He determined to write a drama free from the icy trammels of

classicism. His

Henri III. et sa Cour

was received with unbounded applause, the audience

thinking fit to compliment the author by hooting Racine. Hereupon followed a succession of

plays:

Charles VII.,

Christine,

Antony,

Richard Darlington,

Thérèse,

Angela, all of

which were equally successful. As a novelist M. Dumas attained no less celebrity. Who has

not read

"Monte Cristo" and the

"Three Musketeers" with its continuations,

"Twenty Years After" and the

"Vicomte de Bragolonne," and who can grow

weary of that wonderful

"Edmond Dantès," or of those glorious adventurers,

D'Artagnan, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis?

WE print on the first page of the present number a portrait of the great

romance writer and dramatist, whose death is an event of so much importance as to cause a profound

sensation even in the midst of the desperate struggle now in progress abroad. M. Dumas came of a

strangely mingled stock, which may account for the originality of his genius. His grandfather,

the Marquis de Pailleterie, belonged to the old noblesse of France, his grandmother was a

St. Domingo negress. His father,

M. Alexandre Davy Dumas,

served with distinction in the wars of

the First Napoleon, but after his death his family seems to have fallen into comparative poverty.

The subject of our present memoir was born at Villers-Cotterets, near Soissons, in 1803, and might

have been consigned to a lot of utter obscurity but for the kindness of General Foy. The young

Dumas possessed an accomplishment which is not always associated with literary genius, —he

wrote an excellent hand, and thus obtained a clerkship in the office of the Duke of Orleans's

secretary, with a salary of about £ 50 a year. England

may claim the honor of first stimulating his genius. He had already written a forgotten volume

called

"Nouvelles,"

but it was the sight of Charles Kemble in Hamlet which

set him in the path of success. He determined to write a drama free from the icy trammels of

classicism. His

Henri III. et sa Cour

was received with unbounded applause, the audience

thinking fit to compliment the author by hooting Racine. Hereupon followed a succession of

plays:

Charles VII.,

Christine,

Antony,

Richard Darlington,

Thérèse,

Angela, all of

which were equally successful. As a novelist M. Dumas attained no less celebrity. Who has

not read

"Monte Cristo" and the

"Three Musketeers" with its continuations,

"Twenty Years After" and the

"Vicomte de Bragolonne," and who can grow

weary of that wonderful

"Edmond Dantès," or of those glorious adventurers,

D'Artagnan, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis?