| Le site web Alexandre Dumas père | The Alexandre Dumas père Web Site | |||

|

||||

| Dumas|Oeuvres|Gens|Galerie|Liens | Dumas|Works|People|Gallery|Links | |||

HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE.VOLUME XLVIIJUNE TO NOVEMBER, 1873 NEW YORK HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS 327 TO 335 PEARL STREET FRANKLIN SQUARE 1873 An original scan of this article can be found here. | Alexandre Dumas père Alexandre Dumas fils Jules Sandeau Paul De Kock Théophile Gautier Jules Janin Jules Michelet Octave Feuillet Arsène Houssaye Victorien Sardou Gustave Doré George Sand |

|

| VICTOR HUGO. |

WHAT is not clear is not French, says Voltaire. And yet, in this country, whatever is French is profoundly misunderstood. The language is perspicuity itself, and the American mind is singularly intelligent; but the two have never been introduced ; hence the mutual ignorance. Cultivated persons here as elsewhere are familiar with French character, French genius, and French literature; but the medial intellect knows little of any one of these, and cares less. It considers the French so exceptional that it calls the absence or violation of all ethics French morals, and imagines French literature to be published licentiousness. This is not so strange when we remember how totally unlike are Anglo-Saxon and Gallic traditions, temperament, and thought. French literature, though thinner and poorer, is much bolder and broader conventionally than ours. The French put in print what we say in private; they express our thought, and we, with a silly squeamishness, refuse to admit it. Terrible fellows these Gauls; they are always publishing what we want to hear, what we openly censure and secretly devour. They have the gift of naturalness, and are preserved from hypocrisy. We are favored of form, and resolute to utter the varied phases of our non-belief.

A radical difference between us and the French is that we insist on morality, and they are intent on art. We constantly couple the two; they hold the two have no necessary connection. They represent Nature through the delicate veil of the ideal; we force her into high necks and long skirts—cumbersome raiment, beginning too soon and ending too late. They paint life as they see it; good or bad matters not, so it be true.

We paint life as it should be, indifferent to its truth, provided it be moral. They often seem prurient or indelicate to us. We frequently appear humdrum and tedious to them. They admire us, but wish we would not be so monotonously moral. We are delighted with them, but feel constrained to declare against their absorption by art.

The French, notably the Parisians, are undeniably the most artistic people of modern times; and they are so superlatively conscious of the fact that to tell them it would be like carrying olives to Bologna. They are not to be informed of any thing. What they do not know can hardly be worth knowing. They are intimately acquainted with Paris and all it contains. What lies beyond is unworthy of their attention. This sovereign egotism, this assumption of omniscience, is passing on the Seine. Lutetia has at last discovered her mistake, is laboring to correct it, will labor long, and, in the end, effectually.

It is remarkable how little is popularly known here of French authors. They are seldom translated, for those desirous to read them can do so in the original, and the mass is indifferent to the charm of the polished and treacherous tongue. Original as Rabelais is, profound as Pascal, witty as Voltaire, analytic as Balzac—each a master in his kind—few of the average minds of this country are acquainted with them to any extent. Touching contemporaneous French authors, the general knowledge is still less. It has scarcely heard of The Flowers of Evil, The Forerunners of Socialism, Namouna, or The Comedy of Death; has no definite idea of the productions of Charles Baudelaire, Gérard de Nerval, Alfred de Musset, Théophile Gautier, or fifty other eminent writers who belong to the present generation.

Victor Hugo is so well known that we shall content ourselves with simply placing his portrait at the head of this article.

|

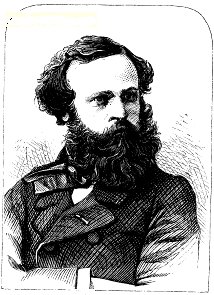

| ALEXANDRE DUMAS, PÈRE. |

Alexandre Dumas the whole novel-reading world knew literally by heart. He was the son of a mulatto general of extraordinary prowess and courage, to whom Napoleon, on account of his single-handed defense of a bridge against the enemy in the battle of Brixen, gave the name of the Horatius Cocles of the Tyrol. Dumas, though the son of a Caucasian woman, was darker than his fighting father, and had many more marks of the mulatto. To his admixture of African blood he owed his vivid imagination, his extreme prodigality, his love of display, and his melodramatic instincts. In his boyhood he was unwilling to study, but became a good shot and swordsman, an expert billiardist, and an excellent equestrian. At fifteen he was a copying clerk in a notary's office at the small town of Villers-Cotterets, where he was born. Even then he began writing plays, and before he was twenty he was obliged to go to Paris to seek his fortune. Aided by a friend of his father, he obtained a small office in the household of Louis Philippe, then Duke of Orleans, and felt himself rich on $250 a year. He then tried to make up for some of the defects of his education 5 wrote & number of vaudevilles anonymously, and even attempted tragedy. When he was twenty-five he brought out Henry III. and his Court, a historical play that discarded all ordinary rules, offended the critics, and pleased the public. In four months he cleared by it $10,000, and found himself on the high-road to fame and fortune. The Tower of Nesle (formerly a stock piece at the principal theatres of the United States), which, though claimed by Frédéric Gaillardet, he produced four years later, enjoyed the extraordinary run of two hundred successive nights.

After establishing his reputation as a dramatist he turned his attention to novels. The Three Guardsmen and The Count of Monte Cristo, printed in 1844, demonstrated his story-telling genius, gave him an immense popularity, and filled his purse with gold. His fecundity was unequaled, as may be seen from the fact that about this time he bound himself to furnish two newspapers annually with manuscript enough to make seventy good-sized volumes, not counting dramas, essays, and miscellaneous articles. It seemed absolutely impossible for any one brain to conceive or any one pair of hands to execute the work he contracted to do; but evidence elicited during a lawsuit proved that, while he made the most liberal use of assistants and labor-saving machinery, he really had sufficient share in his innumerable literary enterprises to justify him in calling them his own.

His capacity for composition and tireless work was altogether abnormal. He wrote faster than a rapid penman could copy, his average daily task being thirty-five pages of a French octavo volume. Stories have been circulated of his having had in Paris a species of mental machine shop, in which clever men wrote, at his suggestion and under his supervision, dramas, travels, novels, histories, brochures, sketches, and memoirs by the dozen, turning them out almost as rapidly as shoes are turned out at Lynn or print cloths at Fall River. Such stories were exaggeratious, but not without a substantial basis of fact. Invention and industry like his had never been known in France or in any other land. He was a miracle of performance, the Samson of scribes. He did not labor so much from literary ambition as for money, of which he was eternally in need. The more he earned (he is said to have been in receipt during the height of his popularity of $30,000, $40,000, and even $50,000 a year) the more he wanted, for his expenditure was unlimited, and his tastes were as extravagant as they were capricious. His purse was open at both ends, yawning to be filled at one and running empty at the other. Gold burned in his pocket, and he hated to be hot. Always earning, constantly working, forever borrowing, ceaselessly lending, eternally in debt, was his normal and unvarying condition. Prudence, economy, provision for the future, were entirely alien to his sanguine and lavish nature. He did not have all he wanted, but he wanted all he did not have. Concern for the morrow was not likely to oppress a man who required nothing except pen, ink, and a few reams of paper for the creation of a princely income. His life was as romantic as the career of his heroes, and his resources were as wonderful. He was at once the autocrat of composition and the padishah of plagiarists. No human being ever carried to greater lengths the assumption of genius claiming its own. All printed matter he held to be his for whatever use he chose to make of it; and yet his intellect was original, fertile, and exhaustless beyond precedent. He simultaneously plundered and enriched imaginative literature; he exasperated and astonished his contemporaries; he impoverished the past and made opulent the present.

Dumas sought to put in practice the things he dreamed of. Ever full of projects, enterprises, expeditions, with all his prodigious work, he was obliged to abandon more than he accomplished. In his forty-fourth year he began to build near. St. Germain a fantastic and costly villa—it was called the Château of Monte Cristo—but the revolution of 1848 and the expulsion of Louis Philippe interfered with his plans and restricted his revenues, compelling the sale, some years later, of his country-seat at less than one-tenth of the original outlay. Though always fond of women, as his father had been before him, he did not legally marry until he was nearly forty, his wife being Ida Ferrier, a vivacious and engaging actress of the Porte St. Martin, with whom he had long been in love.

Among his other follies he published a daily newspaper, The Liberty; but this was too much for him, and he retired worsted from the financial engagement. Then he essayed a review, named The Month, from the time of its issue, and failed in this too. Subsequently he published The Guardsman, revived years after under the title of Monte Cristo, in which he printed his translations, sketches, and romances as they fell hot from his busy brain. The Three Guardsmen and its two sequels—Twenty Tears After and Viscount of Bragelonne—Margaret of Anjou, Memoirs of a Physician, Queen Margot, and Monte Cristo, especially the last, are the most popular of all his works, having been translated into not less than twelve languages. The extent of his productions can not be ascertained; but it is estimated that, including translations and adaptations, he must have been the author of nearly a thousand volumes—far more than the combined works of Lope de Vega, Voltaire, Goethe, and Walter Scott, four of the most prolific writers of modern or mediaeval times.

The chief of romancers has not long been dead. He was to the last the same pleasant, careless, vain, egotistic, wonderful wizard of the pen that he had been for over forty years. Every body knew him in Paris. A thousand eyes followed him when he walked along the Boulevards or drove in the Bois. He fairly beamed with good nature: his stout, full figure shaking with a sort of unctuous satisfaction, and his bright eyes laughing and shedding a glow over his yellow complexion, and kindling his large sensual features from his round heavy chin to the roots of his woolly and bushy hair.

|

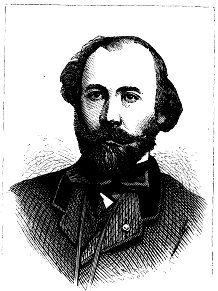

| ALEXANDER DUMAS, FILS. |

Alexandre Dumas, the younger, as he used to be called before the elder's death, is now fifty, and very different from what his father was. Rather irregular in his early youth—otherwise he would not have been a Dumas—he soon found loose morals unremunerative, and based his reformation upon habits the opposite of his parent's. By careful economy and some self-denial he paid all his debts, resolving never to contract anymore; and he has kept his word. While still a boy he was introduced into the society of authors and artists by his father, who was extremely proud, and expectant of his son. At sixteen Alexandre printed a collection of verses, entitled Sins of my Youth, more remarkable for pretension than any thing else. After accompanying his restless parent on his travels through Spain and Africa, he wrote The Adventures of Four Women and a Parrot, and several other novels, which attracted little attention, and thereby disappointed the precocious author.

Discovering his want of the brilliant imagination and superabundant intellectual resources of the elder Dumas, he resolved to cultivate a literary field of his own, and he did so by careful observation and correct delineation of manners. He made a special study of the equivocal society of the French capital; and the first fruit was The Lady of the Camellias—a novel that obtained great and immediate success by the simplicity and pathos of the story and the dramatic character of its incidents. Afterward converted into a play, it was represented at all the theatres of France, and translated into half a dozen languages. It is essentially the same as our well-worn Camille, performed on every stage in this country, from New York to Denver, and from Portland to Galveston. Verdi set it to music under the name of La Traviata, and it may be fairly said that entire civilization wept over the sentimental woes of the consumptive lorette. Dumas's story carried his name every where: he was highly lauded and bitterly censured; but every body admitted he had achieved an astonishing success. The Romance of a Woman, Diane de Lys, The Lady of the Pearls, and Life at Twenty followed the lachrymose novel, and each of them won encomiums, and evinced power, knowledge of human nature, and caustic wit. In their dramatic form they drew crowds in spite, or rather on account, of the severe denunciation they elicited, and the manifest objection that they idealized the demi-monde, and painted its denizens in very seductive colors. He afterward wrote The Question of Money, The Natural Son, and The Prodigal Father, many of the incidents of the latter two having been drawn, it is supposed, from his own experience and circumstances.

Grave considerations of morals enter into all his works, and consequently provoke wide and earnest discussion. He claims to he a philosopher of the iconoclastic school, and a reformer of the Ishmael stamp. One of his latest productions, The Man-Woman, has been widely criticised and commented upon. Dumas is obviously in earnest, and a genuine thinker, albeit his love of paradox and of dramatic effect often gives him an air of artificiality. He resembles his father in face, though not in figure; has a thoughtful and serious expression, and a calm and highly disciplined character. Profiting by parental blunders, he has taken care of his health, his ideas, and his money; has many friends, and a handsome income, wholly the result of his own. industry and of judicious investment.

|

| JULES SANDEAU. |

Jules Sandeau, toward the close of his life, terminated some years ago, did not look like the man whom so intense and romantic and beauty-worshiping a woman as Madame Dudevant would have fallen in love with in her first protest against conventionality. Born at Aubusson, he went to Paris to study law, and forming an intimacy with that fiery and splendid woman, his thoughts were turned to literature. They made their début together in the novel Rose and Blanche, bearing for author the name of Jules Sand. (In the works she wrote alone she borrowed half of his patronymic, and has ever since been known to the literary world as George Sand.) When he was forty-seven he gained the honor dear to every Parisian's heart, a chair in the Academy. Before and after he wrote very clever novels and plays, which enhanced his fame and augmented his ducats. At fifty he was rather fleshy, and would have been mistaken for a prosperous merchant with a tendency to gout. His best novels are Fernand and Madeleine, and his finest dramas Mademoiselle De Seiglière and The House of Penarvan.

|

| PAUL DE KOCK. |

Paul de Kock gained a much worse reputation over here for licentious stories than he deserved, from the spurious and prurient rubbish that used to be put off on the American public as translations of his works. The son of a Dutch banker who perished on the revolutionary scaffold, he received a slender education, and undertook to make himself acquainted with the rudiments and routine of commerce. Such pursuits were distasteful, and he decided at last to pursue literature, believing he could catch it if he ran long and swift enough. Ere he was sixteen he had completed a romance, The Child of my Mother, and unable to secure a publisher, bore the expense of printing it himself. As the public was indifferent to the bantling, the youth devoted his pen to the stage, producing some most melancholy melodramas and flimsy vaudevilles. Thinking he was not appreciated, he returned to his first love, and in two or three years had been responsible for a number of light novels illustrating manners, not always of the best, and peculiar relations of the sexes. Such titles as Gustave, or the Bad Subject, Barber of Paris, Man with Three Pairs of Trowsers, Bashful Lover, A Woman with Three Faces, The Shop-Girl, and The Lady of Three Petticoats indicate the quality of the books. He is responsible for over fifty such works, widely translated, all of them written in an easy, fresh, simple style that has done much for their popularity. Almost eighty at his death, he had an air of substantial comfort, and something of the stolid appearance usually found in the Hollanders. No outward aspect of the Bohemian in him; on the contrary, the suggestions of good sense, thrift, conservatism. De Kock was a great favorite in the Faubourg St. Antoine, but he never made much progress in the Faubourg St. Germain. Privately, he was represented as an amiable, kind-hearted, conscientious man, who often expressed annoyance at the forgeries practiced upon the community in his name, feeling conscious, perhaps, that he had no reputation to spare—as indeed he had not.

|

| THÉOPHILE GAUTIER. |

Théophile Gautier, recently deceased, was a Frenchman in excess, and a very eccentric character withal. Balzac used to declare, with distinguishing egotism, "There are only three of us who write French—myself, Hugo, and Gautier." Born at Tarbes, the Southern sun crept into his blood, and fired his imagination. At fourteen he visited Paris to study, and soon after experienced a passion for the old French language, which is revealed in his style. Forming a friendship with Gérard de Nerval that continued through life, he became an ardent advocate of the romantic school under the leadership of Victor Hugo, and rendered efficient service in the fierce contests which prevailed at the first representations of Hernani. Like many other poets, he fancied his vocation to be painting, and studied it for several years. But, disgusted with the poverty of his first efforts, he threw down the pencil, and seized the pen, affirming that he would make his mark in a still higher department of art. At twenty-two he printed his first volume of verse, followed two years later by a rhyming version of the legend of Albertus, both of which brought him into favorable notice. The Literary France engaged him as a regular contributor ; and he wrote for it, for the Review of Paris, and The Artist some of his most brilliant papers, De Nerval assisting him in his labors.

In 1838 appeared his Comedy of Death, an original and striking poem, strong though ghastly, a strange blending of voluptuous imagination and morbid, sensibility. That fixed his reputation as one of the eminent poets of the country, and extorted praise from some of the most cautious of his contemporaries. Hugo pronounced it an effusion of pure genius, and De Nerval shed tears of joy over its early recognition. The classicists, however, who were his uncompromising foes, violently assaulted the Comedy, and aroused the poet's bitterest resentment. In his preface to Mademoiselle De Maupin, published some time after, he retaliated upon them savagely, and brought upon himself the severe condemnation of a highly intelligent and influential class by his defiance of social opinions and the audacity of his ethics. De Maupin is as brilliant as it is vicious. It seems to have been written, as doubtless it was, to excite the fiercest opposition. In its pages every canon of conventionality is impugned, every conviction of the orthodox ridiculed and degraded. Its entire spirit is pagan, and its scenes of voluptuousness, with which the volume is stuffed, are scarcely removed from the slough of sensuality. The sparkling diction and the extraordinary power of word-painting can not rescue the volume from reprobation. Though still read and admired by scholars, it is one of the books which all prudent parents in France, as well as elsewhere, carefully keep out of their daughters' hands. Gautier never got rid of the odium of the authorship of De Maupin. Years after its appearance it prevented his election to the academy, thus causing him to feel the reaction of his work in his most sensitive part. His chances to be chosen one of the forty immortals had been excellent, but that infamous book, as it was called, forever blighted his prospects.

The Innocent Profligates and A Tear of the Devil are novels in the same vein, though much less objectionable than the one which had excited such wide-spread hostility.

Gautier's travels, for a Frenchman, were quite extensive, and his books on Italy, Russia, and the Orient, interspersed with elaborate and elegant criticisms on art, were deservedly praised by the discriminating, not less than the public at large. He prepared several ballets, the most noted of them The Giselle (Madame Blangy made this memorable here), which still retain possession of the stage.

Gautier in his feeling, mode of thought, range of sympathies, was as essentially pagan as if he had been born in Athens twenty-five centuries ago. He openly proclaimed and was proud of his gentilism, holding that the ancient mythology was quite as true as Christianity, and had an infinite advantage over it through its picturesque quality and its artistic associations. The art sentiment permeated him like his arterial blood—it absorbed and controlled him. He cared nothing for politics, and had few convictions outside of aesthetics. He was by turns a violent republican, an enthusiastic imperialist, an earnest Orleanist, and an ardent devotee of the Bourbons. He was a born image-breaker, and yet one of the most fervid of idealists. Tall, muscular, broad-shouldered, dark-eyed, and black-haired, he marched through the streets of his dearly beloved Lutetia with the look and mien of one who worshiped beauty only, and whose spirit was communing with his cherished gods.

|

| JULES JANIN. |

Jules Janin, one of the most noted of critics, and best known of all the French journalists, continues, in his sixty-ninth year, to define the laws of criticism, and to exercise a profound influence on all matters of art.

Journalism in Paris is a very different thing from what it is in London or New York. On the Seine it scarcely exists in our sense. There it is usually but another name for literature. There all journalists are littérateurs, and most littérateurs, journalists. News, our first consideration, is altogether secondary in France. The readers of a Paris daily are indifferent to a great fire at the Batignolles or a distressing accident on the Lyons Railway, but they can not forgive the omission of a studied criticism of the new ballet at the Gaîté, or of the latest play at the Gymnase. The American turns to the telegrams, and the Parisian to the feuilleton.

In the meaning of the French, Janin is a great journalist; in the meaning of the Americans, he is merely a clever writer and an eminent critic. Born at Côndrieu, the son of an advocate, he studied at the College St. Etienne, where he gave such promise that he was sent to the College of Louis the Great, in Paris, to complete his education. After that, resolving to remain in the capital, he took up his abode with an old aunt, supporting himself by acting as a private tutor. Feeling, however, that journalism was his forte, he wrote upon the drama in some of the minor newspapers, and was afterward introduced to the Figaro by Nestor Roqueplan. From that his course was upward. He founded the Review of Paris and The Children's Journal (I translate titles literally, even though they convey a very different impression in the vernacular), and about the same time finished his virgin romance, fantastically christening it The Dead Ass and the Beheaded Woman. Taking an active part in politics, without manifesting remarkable steadfastness or consistency, he finally became the dramatic critic of the Journal of Debates, where he has since exercised an enormous influence. He soon grew to be, what he modestly called himself, the prince of criticism, and without any declaration of principles, by the right of his mind, established Janin as the most arbitrary and absolute of sovereigns.

In his thirty-seventh year he married a wealthy heiress, both young and pretty, and had the ill taste to give, soon after, in the place of his regular feuilleton, a rose-colored account of his wedded happiness, under the title of The Marriage of the Critic. This rendered him ridiculous—it is a serious thing to be made ridiculous in Paris—and, provoking very satirical and cutting comments on the part of his contemporaries, made the happy bridegroom for a while a very unhappy critic.

Janin's vanity and egotism have always been unbounded. Among a thousand other assumptions, he claims to have made the great tragédienne Rachel. When she had been induced by vast sums of money to visit this country on a professional tour, he scolded her through his columns very much as if she had been a little child bent on eating lobster-salad before going to bed. Not satisfied with this, he abused the republic in all the diversities of French revilement, declaring us a set of barbarians, wholly incapable of comprehending Corneille or Racine, and unable to distinguish between Agamemnon and an Apache Indian. He never forgave the artiste for coming here, and was ungenerous enough to say, privately, that she deserved her death, which resulted from a cold contracted during her engagement in Charleston, South Carolina.

Janin has been a very prolific author, writing on almost every subject, and always with such emphasis of opinion and supreme self-consciousness as to indicate his belief that the globe would cease to revolve but for the expression of his judgment. His complete works would make more than one hundred good-sized volumes, and his prefaces, introductions, essays, and commentaries to and upon other books would, if collected, be a conspicuous monument to his industry and his egotism.

A rotund, corpulent critic is he, measuring almost as much diametrically as vertically. Genial in manners, he is often very caustic with his pen, which has the reputation of flowing with gall or honey, just as the writer has been defied or propitiated. He is bitter when he thinks of those too stupid to admire him, and gracious when occupied with the delightful and customary task of taking his own altitude. If ever man felt inclined to remove his hat on beholding his reflection in a mirror, that man is Jules Janin.

|

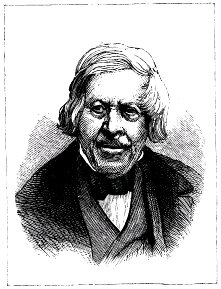

| JULES MICHELET. |

Jules Michelet, the historian, carries his age gracefully, being now seventy-five, and yet so full of literary projects that he could hardly complete them should he live to be twice a centenarian. The son of a banknote printer, he was called at twenty-three to the chair of history at the Rollin College, in Paris, where he lectured also on the ancient languages and on philosophy, holding the position for five years. The revolution of 1830 secured to him the very desirable position of chief of the historical division of the Archives of the kingdom. At the same time Guizot chose him as his assistant at the Sorbonne, and Louis Philippe made him professor of history to his daughter, the Princess Clementine. A little later he published the first volume of his History of France, followed by a series of historical works, resulting in his occupation of a chair of ethics and history in the College of France and in the Academy of the Moral Sciences. In this position, sustained by the sympathies of the young men of the time, he began his brilliant propagandism in favor of democracy, and especially against the Jesuits, which excited against him among the ultramontanists of the Continent such a determined animosity. The fruit of his zeal was three books, called The Jesuits, The Priest of the Wife and Family, and The People. In 1847 was published the initial volume of his History of the Revolution, and the following year he was nominated by the liberal party to the Chamber of Deputies; but he declined to be a candidate. Meanwhile he continued to teach at the College of France his democratic doctrines, and this caused the government to close his course of lectures. The ensuing December he resigned his place in the Archives. Since his second marriage—his present wife is represented as a remarkably charming and lovely woman—he has varied his severe labors by the composition of such lighter works as Love, The Bird, The Insect, Woman, and The Sea. These are very daintily and eloquently written; and two of them, Love and Woman, notwithstanding their excess of sentiment, show such a delicate understanding of the sex, and such a beautiful spirit of chivalry, as to merit all their commendation.

Michelet's histories make a long list. As a historian, he stands, in France, in the front rank; as a man, his position is equally assured. An ardent republican, and a devoted patriot, his sympathies comprehend the whole race, and his belief and aspirations are such as are recorded in his Bible of Humanity.

|

| OCTAVE FEUILLET. |

Octave Feuillet, just turned of sixty, is best known in this country as the author of The Romance of a Poor Young Man, familiar both as a novel and a drama. He has published not less than fifty or sixty novels, comedies, vaudevilles, and scenes of phantasy, nearly all of which have received a warm welcome in Paris, where he has resided since his early boyhood. Though the son of a captain-general of prefecture, he owes his advancement to his own exertions, and his success in literature to a high order of intellect and indefatigable industry. Once, when he was complaining that some of his later books had not sold as well as they ought to sell, his wife told him they were too pure to be popular—that the public preferred printed wickedness to any thing else. The consequence was Camors, which was eagerly purchased, and of which a translation in English has found here a host of readers.

Madame Feuillet evidently understands the world.

Feuillet is a thorough-paced Frenchman, and hates the Germans as vehemently as any Frenchman should. It will be remembered that, just after the close of the war, he was arrested on the frontier by the enemies of his country for some severe strictures he had published upon them, and that he took advantage of his temporary imprisonment to wrap himself, metaphorically, in the tricolor, and to become typographically epigrammatic at the expense of the barbarous foe. Feuillet has a calm, fine, strong face, was decidedly handsome in his youth, and his manners and address are reposeful and attractive.

|

| ARSÈNE HOUSSAYE. |

One of the most elegant and entertaining of contemporaneous French authors is Arsène Houssaye, sprung from an ancient line of agriculturists, and allied by blood to the famous Condorcet. A native of the little town of Bruyeres, he made his début in Paris in good season, and at twenty-one appeared in print as the writer of two romances, The Fair Sinner and The Kingdom of the Blue-Bottles. The friendship of Jules Janin, Théophile Gautier, and Jules Sandeau materially aided him in his literary advancement, and he soon acquired vogue and favor as an art critic. In 1849 he was indebted to the support of Rachel for the place of administrator of the French Comedy, which he managed so well that the theatre, though it had had a very large debt, attained a remarkable degree of prosperity. He caused to be presented many of the best works of Hugo, Dumas, Ponsard, Augier, Musset, Mallefille, Gozlan, and others, and the period of his direction was regarded as a revival of true dramatic art. In many of his books the style and manner of thought of the age of Louis XV. are reproduced, and the stately grace and artificial refinement of the epoch, well preserved.

Philosophers and Actresses, one of his best-known books, gives a very correct idea of his literary treatment and epigrammatic diction. His talent has been described by Philarète Chasles as a smile tempered by a tear, and a turn of wit softened by a stroke of sentiment. The Eleven Forlorn Mistresses, The Journey to my Window, and The Daughters of Eve are exceedingly clever stories, marked by the fantastic quality and pointed ease characteristic of the author. Houssaye, now in his fifty-eighth year, is actively engaged upon several novels, the scenes and characters taken from the great but brief war which so bitterly humiliated the pride of France. He much resembles, and is often mistaken for, an American, and his uniform amiability and engaging manners have endeared him to a wide circle of widely divergent friends.

|

| VICTORIEN SARDOU. |

The most successful, though not the cleverest, of Parisian dramatists just at present is Victorien Sardou, who has the knack of pleasing popular audiences by seizing upon the prevailing idea, and adapting it to the temper and the taste of the multitude. A native of Paris, he studied medicine at first, but soon gave it up to devote himself specially to the investigation of history. Having no means, he gave instructions, in order to support himself, in philosophy and mathematics, wrote articles for the reviews and the minor journals, and put upon the boards of the Odéon a comedy named The Student's Tavern. The piece was generally condemned before the end of the first act, causing such bitter mortification and disappointment to the young author that he did not enter the theatre again for two years.

In his twenty-eighth year he married Mademoiselle De Brécourt, whose greenroom relations were intimate, and who introduced him to the ancient immortal, Déjazet. The veteran actress encouraged him to try again, and offered him all possible inducements to produce another play at the theatre bearing her name. His second attempt went far beyond his most ardent expectations, and from that time his reputation has been growing and his purse swelling. Among his best dramas are Our Particular Friends and The Benoiton Family. There is no end to his stage productions, nearly all of which are composed with a rapidity, not to say precipitation, that precludes exactness of delineation and finish in detail. Most of them are remarkable for reminiscence, and the author, in consequence, is repeatedly accused of wholesale borrowing. His dramas have a good deal of movement, and the characters certain striking features that insure appreciation from the masses. A number of them have been given here, but with less success than in Paris, where whatever appears under his name is almost certain to draw. He is reputed to be an extraordinary medium, having long felt a deep interest, and cherished a firm belief, in spiritualism. One of the youngest of the prominent French authors—he is but forty-two—he enjoys a larger income from the theatres than any playwright in Europe. His face denotes Hebrew extraction, and some of his envious rivals are fond of calling him the cunning Israelite who makes dramatic brass watches with stolen works, and adroitly puts them off as gold upon an undiscriminating public.

|

| GUSTAVE DORÉ. |

A marvel of industry and production is Gustave Doré, who does so much that one would imagine he had the power of multiplying himself. He is forty-three, an Alsacian, a paragon of good nature, and a delightful companion withal when he is fairly out of harness. His illustrations are so far superior to his paintings that he is seldom thought of as a painter. He has illustrated Rabelais, Sue, Balzac, Montaigne, Dante, Cervantes, Taine, and many others, and bids fair, should he live forty years longer, to illustrate all the famous authors of the past and present. His reputation it world-wide, and he has ten times as many orders as he can fill. He is said to earn from 200,000 to 250,000 francs per annum, and he might augment his income fiftyfold if he only had as many hands as Briareus. Of late years his manner has become almost if not quite mannerism, which, while it may add to the individuality of his sketches, renders them unpleasantly monotonous. In temperament and in semblance Doré is rather German. He looks younger than he is; has a broad face, small eyes, high cheek-bones, wears only a mustache, and smokes like a Spaniard.

|

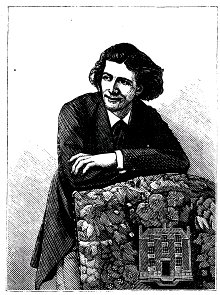

| GEORGE SAND. |

Of the gifted and world-famous woman, Aurora Dupin Dudevant, known to two hemispheres as George Sand, little need be said, since volumes have been written in praise of her genius and in attempted analysis of her character. She is descended on her father's side from Maurice de Saxe, natural son of Augustus II., King of Poland, and Aurora of Konigsmark. Her father dying when she was a child, she was left to the charge of her grandmother, who never understood her, and whom she always disliked. Removed from Paris, where she was born, to the country-seat of the family—it was called Nohant—near La Châtre, she led an irregular, moody, and eccentric life. Her understanding and imagination were abnormally developed. At ten years of age she had the thoughts and feelings of a woman, and at fourteen was a philosopher and a sage. She spent two years at a fashionable boarding-school in the capital, where, her unsettled and unhappy condition of mind having been taken the usual advantage of, she was duly proselyted into the Roman Catholic Church. She even contemplated entering a convent, and would have done so but for some fortunate circumstance which sent her back to Nohant before she was sixteen. Her grandmother's death was the cause of her going to reside with some friends near Melun. There she became acquainted with a young man, Casimir Dudevant, to whom she was married at eighteen.

He was one of the last men she should have wedded, but he was attentive to her. Her heart was on fire, her poetic brain transfigured him, and the quivering soul of genius fell to the keeping of a conventional and commonplace husband. The result was inevitable. They could not coalesce any more than the ivy and the cabbage, and in a few months they were so spiritually divorced that all the laws of civilization could not have held them together. Her growing melancholy and feverish unrest made her long for excitement which would enable her to forget herself. She was starving for Paris, where she hoped to support herself, inasmuch as her liege had already lost most of her fortune in injudicious speculations. He consented to her spending half the time in the capital, and she flew thither like a liberated bird.

There, as has been said, she wrote her first novel in conjunction with Jules Sandeau. Then, unaided, she produced Indiana. which created a genuine sensation. Lélia, the boldest and perhaps the most striking of all her works, followed, and frightened those it did not fascinate. The name of George Sand was on every body's lips, and the rumor that she was a woman intensified the interest in her. She had by this time resolvied to break through conventionality, and live, as she expressed it, in harmony with God and her own soul. She had many gifted companions and intimate friends. She went to Italy with Alfred de Musset; she learned the profundities of law from Michel de Bourges, the inconsistencies of theology from, Lamennais, the doctrines of socialism from Pierre Leroux, the mysticism of music from Frédéric Chopin, and the broadest republicanism from Ledru-Rollin.

Her history is that of a strong and fervid soul, misguided perhaps, but struggling upward to the light. She has been misrepresented and abused, though to-day most unprejudiced minds give her credit for purity of motive and sincerity of purpose. Beautiful in her youth, she is no longer so; but her face is attractive from its geniality of expression and the singular brightness of her ever-changing eyes. Her History of my Life is one of the most spiritual and profoundly interesting works ever written. No one can read it without feeling the power and the virtue of the woman. This passage is impressive: "My religion has never essentially varied. The forms of the past have vanished for me, as for my age, in the light of reflection; but the eternal doctrine of all believers, the goodness of God, the immortality of the soul, and the hope of another world, have resisted all investigation, all discussion, and even the intervals of despairing doubt."