| Le site web Alexandre Dumas père | The Alexandre Dumas père Web Site | |||

|

||||

| Dumas|Oeuvres|Gens|Galerie|Liens | Dumas|Works|People|Gallery|Links | |||

[This article is from the National Magazine for February, 1905.]

|

CARTOON OF LA MENKEN IN THE SHOW WINDOWS FORTY YEARS AGO |

LA BELLE MENKEN

By CHARLES WARREN STODDARD

Author of "South Sea Idyls", "Exits and Entrances", etc.

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

IT was away back in the early sixties: San Francisco, California, was not yet sixteen, but she was precocious, and her hot blood leaped from hearts that were not unfrequently pierced on the shortest possible notice by vengeful bullet or stiletto. The town was billed with posters heralding the approach of "The Menken," La Belle Menken, Adah Isaacs Menken, with her "Mazeppa" and "French Spy," two picturesque impersonations that she was destined to make world-famous.

The windows of nearly every shop in the city framed a startling cartoon that caught the eye on the instant, and if the masculine observer was still heart-whole and fancy-free, it probably gave him something to think about for some time to come.

It was the portrait of a young and beautiful woman that was turning the heads of the people just then. A striking picture, it was, far out of the common run in that day: a head of Byronic mold a fair, proud throat, quite open to admiration, for the sailor collar that might have graced the wardrobe of the Poet-Lord was carelessly knotted upon the bosom with a voluminously flowing silk tie. The hair, black, glossy, short and curly, gave to the head, forehead and nape of the neck a half-feminine masculinity suggestive of the Apollo Belvedere.

The eyes were what transfixed one at first sight, for they were not wholly human. Often they were referred to as those "intoxicated eyes"; perhaps they were intoxicated once in a while; certainly they were intoxicating so long as they chose to shed their almost lurid light upon the young and easily impressionable. This is how they affected Charles Reade, the novelist, in his maturity. In his memoir, the chapter entitled "Friends, Fautors and Favorites," he says of the Menken: "A clever woman with beautiful eyes—very dark blue. A bad actress, but made a hit by playing 'Mazeppa' in tights. She played one scene in 'Black Eyed Susan' with true feeling. A trigamist, or quadrigamist, her last husband, I believe, was John Heenan, the prize-fighter. Menken talked well and was very intelligent. She spoiled her looks off the stage with white lead, or whatever it is these idiots of women wear. She did not rouge, but played some deviltry with her glorious eyes, which altogether made her spectral. She wrote poetry. It was as bad as other peoples would have been worse if it could. 'Requiescat in pace.' Goodish heart. Loose conduct. Gone!"

There is a bad epitaph for you; quite in the vein of Tom Carlyle. In sooth the ill repute of her fellow players could have hardly matched it.

![]()

|

MENKEN AS THE ARAB BOY IN "THE FRENCH SPY" |

The chief theater of the metropolis, Maguire's Opera House, was packed to the tune of sixteen hundred and forty dollars in coin on that first night, when "Mazeppa," apparently stripped to the buff, was lashed to a wild horse of Tartary that was really worthy of the name.

There have been "Mazeppas" and "Mazeppas" in this wicked world of ours, all feminine and mostly fat—though I once saw Joe Jefferson play a burlesque "Mazeppa," in that same opera house: clad in fleshings, he was lashed to a rocking-horse and pushed across the stage on castors.

|

MENKEN AS MAZEPPA |

The average "Mazeppa" is about as much as an ordinary horse can carry; the animal in his famous flight over the Mountains of the Moon ambles up an inclined tow-path as if he were on a pious pilgrimage, and his only fear is that he may not reach the "flies" in season to secure a succulent reward at the hands of the impending stable-boy. He comes of a family every member of which seems to have been born with a padded back as flat as a table and as soft as a feather-bed. Not so the Menken's fiery steed; he was a very spirited beast, evidently proud of the beauty and the bravery of his living burden. She loved him for the dangers he had passed with her and so, nightly and at the matinees, she risked her life that she might thrill her breathless audience and fill the pocket she had left behind her in her undressing room.

Charles Henry Webb, poet and wit, said in his "Californian"—the brightest weekly in the history of early California literature:—" The Menken is unrivaled in her particular line—but it isn't a clothes-line."

Garments seemed almost to profane her, as they do a statue. She was statuesque in the noblest sense of the word. It was impossible to think of her as being fleshly, or gross, or as even capable in anywise of suggesting a thought tinged with vulgarity. The moment she entered upon the scene she inspired it with a poetic atmosphere that appealed to one's love of beauty, and satisfied it. She was the embodiment of physical grace. She possessed the lithe sinuosity of body that fascinates us in the panther and the leopard when in motion. Every curve of her limbs was as appealing as a line in a Persian love song. She was a vision of celestial harmony made manifest in the flesh—a living and breathing poem that set the heart to music and throbbed rhythmically to a passion that was as splendid as it was pure.

I saw her as a boy, and she inspired in me an enthusiasm that found expression in some youthful verses championing her cause. She had been cried down by critics because she had lived a life that was to say the least unconventional. She had been insulted by low minded brutes who were not worthy to loosen the thongs of her sandals. To the "'prurient prudes" she had become a scorn and a hissing. I knew her story as it was known of men, but it did not appal me: it woke in me the pity that is akin to love. I am glad that it did then; I am glad that the memory of that emotion does even at this late day.

![]()

|

|

|

MENKEN IN "THE CHILD OF THE SUN" |

Adah, the subject of this sketch, was born in a little village on the shore of Lake Chartrain, near New Orleans, Louisiana, on the fifteenth of June, 1835. Her father, Mr. James McCord, was a merchant in good standing, who died, leaving three children, of whom Adah was the eldest. Adah's father had always been an ardent admirer of Terpsichore, and almost as soon as they were able to toddle his children were placed in charge of a French dancing master. Mr. McCord died when Adah was seven years of age, leaving his family in straitened circumstances, The widow placed her two daughters in the ballet at the French Opera House, New Orleans, where, as infant phenomena, they made a success. Later, with the Monplaisir Troupe, Adah visited Havana and became so great a favorite that she was popularly known as the "Queen of the Plaza. " She played a brilliant engagement in the leading opera house of the City of Mexico. She returned to New Orleans and retired from the stage, as was her wont at intervals, begin always divided against herself.

In Galveston, Texas, in 1856, she married Alexander Isaacs Menken, a musician. She returned to the Varieties Theater, New Orleans, starring in "Fazio, or The Italian Wife"; but again retired and began the study of sculpture in the studio of T. D. Jones, at Columbus, Ohio. Under the pen-name of "Indigina," she published a volume of poems entitled "Memories." She was on and off the stage at intervals, playing engagements in various companies in many different cities, or devoting herself for a time to painting, poetry, or sculpture.

Her husband having died, Menken was married, April 3, 1859, to John C. Heenan, a prize-fighter, known to the sporting world as "the Benicia Boy." They were married by the Rev. J. S. Baldwin at the Rock Cottage, on the Bloomingdale Road, near New York City; from him she was divorced in 1862, by an Indiana court. She married Robert H. Newell—at one time widely known as "Orpheus C. Kerr," the humorist; was divorced from Mr. Newell in 1865. In 1866 she married Mr. James Barclay, who survived her.

|

|

|

MENKEN AS WILLIAM IN "BLACK EYED SUSAN" |

The Menken played engagements that may almost be called sensational; they were great financial successes, created unbounded enthusiasm and were the subject of sometimes violent discussion. As "Mazeppa" her impersonation was brilliant and startling; as the Arab boy in "The French Spy," she was the apotheosis of poesy. As William, a sailor, in "Black Eyed Susan," even Charles Reade acknowledged her ability in "one scene." The truth is the Menken's William, a sailor, in that dear old obsolete, semi-melodramatic idyl of the Fleet, was a wonder; of course there never was anything like it on ship or shore. There never could have been anything like it to last more than a minute after the fall of the curtain. A sailor boy so dainty and delightful as this sweet William would have been devoured by the sweethearts in any port, or even petted to death by the crustacea on a desert island. However, the interesting fact remains that, as an embodiment of all that was deliciously melancholy, melodious, and unmasculine, the memory of that particular Wiliam is immortal; and if such a sailor had ever sailed the enchanted seas in the age of fable he would probably have dragged the sirens of Scylla and Charybdis out of their scaly attenuations like boiled shrimps.

In "The Child of the Sun," a play written for her by John Brougham, she was singularly picturesque; and in "Les Pirates de la Savanne," a play written expressly for her Paris engagement by Ferdinand Dugue and Anicet Bourgeois, and produced at the Theater de la Gaite, she dazzled and delighted the natives.

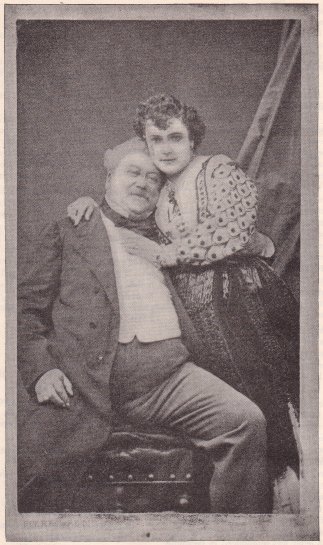

The Menken made her final exit from the stage of the world while photography was still in its infancy, yet she was constantly posing at the request of photographers who were making little fortunes out of the sale of these pictures. Sarony, alone, took some hundreds of different poses, but the pictures are all small, of the old-fashioned carte de visit size, and they are but poor specimens of art. Those here reproduced have been in my possession forty years—save only the one of Dumas and Menken, which was taken three or four years later than the others.

![]()

That Adah Isaacs Menken was a woman of unusual talent is beyond question. She may not have been a genius, but her nature was of that difficult sort that is near allied to the madness of genius. She proved this in everything she said or wrote or did. Her chirography advertises the fact; and if the handwriting of a person is the index to his character, hers was one to call forth the sympathy of all Christian souls. It has been thus interpreted by a friend, at my request:—Nature gave her the joy of sensations; to all the senses she responded easily, and each thrilled her; a creature of real refinement; possessed of much natural delicacy—yet with moments when the physical got the better of the spiritual; tactful, sincere, witty, with an appreciation of the ludicrous, and liking to chaff a little; not without a touch of coquetry; of quick perception, sometimes arriving at profound truths as by a short cut—intuitively; kind, generous, simple, unaffected, but with profound and lofty emotions and at times almost mystical; unaffected, yet occasionally having an air of affectation. A natural capacity for taking pains; fond of detail, all her impersonations showing clever conceptions carefully carried out. Prone to melancholy; not easily hopeful; possessing a grace in repose as satisfying to the eye as a chef-d'-oeuvre in sculpture. One seer pronounced her the victim of a deeply religious and spiritual nature perpetually at war with the flesh that overwhelmed it.

Her bosom friend, Ada Clare, known in the palmy days at Pfaff's as the "Queen of Bohemia," told me that once when she wished to walk with the Menken, who was about to take her afternoon promenade, the latter said to her: "No, dear! do not be seen in public with me, you have to establish your reputation in this place and to be seen with me might hurt it."

![]()

Once she sang in this strain:

|

MYSELF Now I gloss my face with laughter, and sail my voice on with the tide. Decked in jewels and lace, I laugh beneath the gas-light's glare, and quaff the purple wine. But the minor-keyed soul is standing naked and hungry upon one of heaven's high hills of light. Standing and waiting for the blood of the feast! Starving for one poor word! Waiting for God to launch out some beacon on the boundless shores of this Night. Shivering for the uprising of some soft wing under which I may creep, lizard-like, to warmth and rest. Waiting! Starving and shivering. Still I trim my white bosom with crimson roses; for none shall see the thorns. I bind my aching brow with a jeweled crown, that none shall see the iron one beneath. My silver-sandaled feet keep impatient time to the music, because I cannot be calm. I laugh at earth's passion-fever of Love; yet I know that God is near to the soul on the hill, and hears the ceaseless ebb and flow of a hopeless love, through all my laughter. But if I can cheat my heart with the old comfort, that love can be forgotten, is it not better? After all, living is but to play a part!

Yet through all this I know that night will roll back from the still, gray plain of heaven, and that my triumph shall rise sweet with the dawn! When these mortal mists shall unclothe the world, then shall I be known as I am! When I dare be dead and buried behind a wall of wings, then shall he know me! When this world shall fall, like some old ghost, wrapped in the black skirts of the wind, down into the fathomless eternity of fire, then shall souls uprise! When God shall lift the frozen seal from struggling voices, then shall we speak! When the purple and gold of our inner natures shall be lifted up in the Eternity of Truth, then will love be mine! I can wait! |

Thus she stormed high heaven, or bewailed her fate in rhapsodies that sometimes verge upon frenzy and sometimes seem the despairing cry of a lost and loving soul.

![]()

Her imagination was of a lurid cast; it had feasted upon and echoed the wild and wayward rhythm of the Psalms of David and Walt Whitman's "Leaves of Grass." In her little book of verses "Infelicia," there are few lines that are, not more or less inflated, some that are truly noble, and some that are poor enough. This volume of one hundred and twenty-four pages was dedicated to Charles Dickens "by permission"; the permission gracefully granted in an autograph letter was reproduced in facsimile as a frontispiece to the first edition of the poems, but afterward suppressed:

It ran as follows:

|

GAD'S HILL PLACE, HIGHAM BY ROCHESTER, KENT. Monday, Twenty-first October, 1867. Dear Miss Menken, CHARLES DICKENS. |

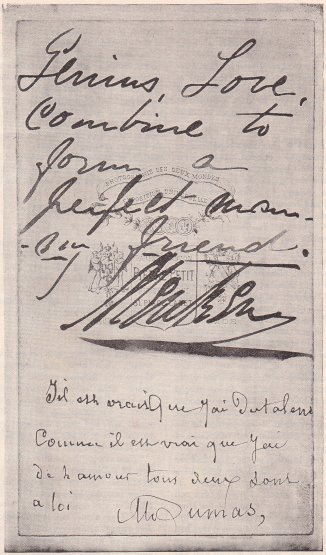

That Adah Menken could write simply and sweetly is evidenced by the following lines which she very kindly wrote for me in an old-fashioned album, the pride of my youth. They are written in a band that is highly characteristic: a free hand of large swinging curves flowing bravely from a stubby quill; the i's dotted with bullets, the t's crossed with javelins, the flourish after her signature as long and elaborately curlicued as the whip-lash of a Wild West cow-boy.

|

THE POET The poet's noblest duty is, That, howso'er despised may be For deepest in creation's midst And, with poetic instinct fired, A. I. MENKEN. |

![]()

|

THE FAMOUS PHOTOGRAPH OF MENKEN AND DUMAS, THE ELDER, TAKEN FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION ONLY, BUT IMITATED AND CARICATURED AND SOLD EVERYWHERE IN PARIS |

|

AUTOGRAPHS OF MENKEN AND DUMAS ON THE BACK OF MR. STODDARD'S COPY OF THE PRECEDING PHOTOGRAPH |

Menken made many friends among the literary and artistic celebrities of London and Paris. It was rumored that the poet Swinburne and many of the lesser literary lights of London had fallen under her spell. After her death, when infamous libels were printed freely and her name became a jest on the lips of scoffers, more than one clergyman stood up in indignation to utter a protest in the name of chivalry and of common humanity.

![]()

It is easy to lose one's reputation in the glare of the footlights. If they were to turn their blinding rays upon the inquisitive throngs in the pit, the boxes or the gallery, how many revelations would add interest to the inner lives of our nameless neighbors.

As for the much discussed photograph of Menken and Dumas, the elder, the only original is here reproduced. Its history is this: They were photographed for their own pleasure and for the pleasure of their friends, and the picture was never intended for publication. Someone obtained a copy—no copies were for sale—and finding a man and woman with figures resembling the originals, these were posed like lay figures in several attitudes, some of them quite indecent; faces of Dumas and Menken were attached to the figures, the whole rephotographed and the copies offered to the public. The shops were flooded with them and though an effort was made to suppress them, it was decided by the courts that they came under the head of caricatures and the sale went on.

All this breathes of the days that are no more. Then came the story of a great feast that ended with a fatality. It was told how, bereft of friends, sick and in poverty, the wasted body of the Menken was borne to a nameless grave, followed only by the noble animal that had played his part so many times with her in "Mazeppa," and one servant who was faithful unto death.

This was in no wise the case. Adah Isaacs Menken died peacefully in the Paris that she loved, on the tenth of August, 1868, attended by the ministers of her adopted faith, the Jewish.

So, many years ago, passed from mortal vision all that was known to the pleasure-loving public as La Belle Menken. For a little time her body lay in the stranger's burying-ground at Pere la Chaise, but later it was removed to Mont Parnasse cemetery, where it now lies, a handful of dust, hidden away in an obscure corner; and above it, cut in marble, as she desired that it should be, her final appeal to her Creator, her farewell to the uncharitable world—her last word—

"THOU KNOWEST!"

![]()

I want to add to this tribute something of her own; something as characteristic as anything she ever gave to the reading world. It was, of course, not intended for publication, but I feel sure she will forgive since it so pathetically appeals to all who would believe in her goodness:

|

"My Poet— "Your letter and poems came just today, when kind and beautiful things were so much needed in my heart. That letter and your thrilling poems have fulfilled their mission: I am lifted out of my sad, lonely self, and reach my heart up to the affinity of the true, which is always the beautiful. "I am not in the condition to tell you all the impressions your poems have made upon me. I have today fallen into the bitterness of a sad, reflective and desolate mood. You know I am alone, and that I work, and without sympathy; and that the unshrined ghosts of wasted hours and of lost loves are always tugging at my heart. "I know your soul! It has met mine somewhere in the starry highway of thought. You must often meet me, for I am a vagabond of fancy without name or aim. I was born a dweller in tents; a reveler in the 'tented habitation of war '; consequently, dear poet, my views of life and things are rather disreputable in the eyes of the 'just'. I am always in bad odor with people who don't know me, and startle those who do. Alas! "I am a fair classical scholar, not a bad linguist, can paint a respectable portrait of a good head and face, can write a little and have made successes in sculpture; but for all these blind instincts for art, I am still a vagabond, of no use to anyone in the world—and never shall be. People always find me out and then find fault with God because I have gifts denied to them. I cannot help that. The body and the soul don't fit each other; they are always in a 'scramble.' I have long since ceased to contend with the world; it bores me horribly; nothing but hard work saves me from myself. "I send you a treasure: the portrait and autograph of my friend, Alexander Dumas. Value it for his sake, as well as for the sake of the poor girl he honors with his love. O! how I wish that you could know him! You could understand his great soul so well—the King of Romance, the Child of Gentleness and Love: take him to your heart forever! "In a few days I shall see him, and then a pleasant hour shall be made by reading in my weak translation what I like best in your poems. We always read and analyze our dearest friends—but Alexander is too generous to be critical. "I shall not remain here long. Vienna is detestable beyond expression. Ah! my comrade; Paris is, after all, the heart of the world. Know Paris and die. "And now, farewell! Let me try to help you with my encouragement and the best feelings of my heart. Think of me. I am with you in spirit. Your future is to be glorious. Heaven bless you. Infelex, MENKEN." |

![]()

It is perhaps not surprising that a letter of this character, whether it was the spontaneous outpouring of an impulsive and ingenuous heart, or merely the pose of an artful woman who courted admiration and would have it at any cost, should touch the vanity of a young fellow barely out of his teens and swear him her liege forever. I believe that it was a generous spirit that prompted the writing of it; I know that her delicate flattery did not hurt him in the least, though she was at that time one of the most famous women of the world, the bright, particular star dazzling two continents, and he merely an aspiring poet-aster. On the contrary, it inspired him to nobler efforts and filled him with a longing to achieve something worthy of her praise.

When the news of her sudden and untimely taking off was borne across the sea, there was grief profound in at least one breast, by the shore of the far Pacific, and his lute was touched with a trembling hand.

His lines were not worthy of her, nor of anyone else; they were but a poor echo of Tennyson who was then his lord and master, but he had not yet forsworn the gentle art; he was not the reformed poet that he later on became, and perhaps nothing could better prove his wisdom in that voluntary reformation than the lines themselves—so here they are:

|

LA BELLE MENKEN "THE BODY AND THE SOUL DO NOT FIT EACH OTHER." Poor martyr-soul, that was condemned To solemn ways unreconciled; O, tropic blossom, tempest-tost! And all thy splendid forces spent; Now half the world will scorn thy fate, Now dumb within thy shroud of snow, But whoso hath a spirit free And never he whose faith is sure AUGUST, 1868. |